Brands are no longer competing just for patronage, they are competing for attention on about six inches of real estate, says the author.

In 2009, Apple came up with a phrase that was a foreshadowing of how our purchasing patterns would be forever altered – ‘there’s an app for that’. Since then, smartphone apps have branched out into almost every industry. In the ‘good old days’, options for purchase would require us to shuffle between shops, speak to the staff, bargain to get the best deals, and finally make their choice. Today, options for each specific app exist within our app drawers.

Research shows that, on average, a smartphone user has around 80 apps installed. Knowing that their competition is just a touch away, brands are adapting and adding to their core offerings by looking outside their core category of expertise (Swiggy for example, has added groceries and intra-city deliveries) to get more people into their ecosystem. Brands are no longer competing just for patronage, they are competing for attention on about six inches of real estate. With the conversations around super apps, we are moving from ‘this one’ to the ‘most convenient one’.

The psychology of convenience

As slaves to modern society, we live in an increasingly fast-paced environment where we have to make decisions as part of a demanding lifestyle – multiple roles, WFH, and long hours. When it comes to making decisions we rely on two types of guides in our mind:

- The analytical guide – What we use the majority of the time to work things out properly and decide. It is conscious, controlled, calculated, and requires a lot of effort.

- The intuitive guide – What we use when reflexively making snap decisions – ‘gut feeling’. It is unconscious, automatic, and doesn’t require effort.

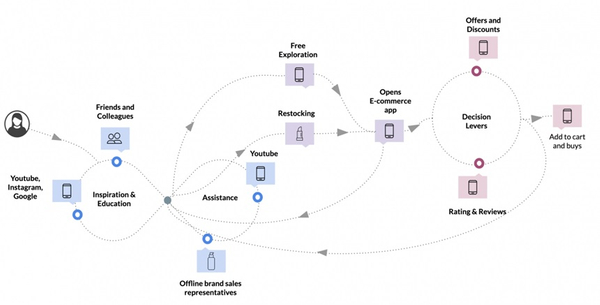

Today, our purchase journey has become more and more complicated:

With limited rationality and willpower, as the complexity of the journey increases, our decision making becomes susceptible to one of four influences:

- Aspiration – Seeking to be better versions of us

- Manipulation – Influenced by marketing

- Instinct – Impulse buying

- Decision fatigue – Overload of information

In the latter two states, when we try to make a purchase decision about comparatively smaller things (food for lunch, for example) our minds automatically rely on the intuitive guide to help find easier ways to make a decision – we are wired to seek convenience.

This has become even more prevalent as mobile and online ordering facilities have brought a level of convenience for all our needs that weren’t there before – make your choice, pay and arrange delivery or collection from your smartphone or computer. Thus, allowing us to quickly and easily get what we want when we want it:

- 97% of shoppers reported having backed out of making a purchase because of inconvenience.

- 87% of Indian shoppers reported that they are willing to pay a premium to get convenience.

Which makes sense as services like Prime have become an almost default subscription. As a thumb rule, ‘easy and fast’ makes a tired brain happy. Apps have ensured we are reliant on them to experience easier decision-making.

Three eras of retail

As a major disruptor, digital, was expected to completely swallow offline businesses (as feared by people with torches and pitchforks). But what it has actually led to is more Darwinistic. It has taught us to adapt to convenience and induced a long-term change in our behaviours. When it comes to the retail ecosystem, as consumers, we have gone through three major eras:

The offline retail era

The era of traditional retail where signs claiming ‘Customer is king’ were hung proudly behind cash counters. King, we may be, but the real power lay with the retailers/owners who controlled how the business would run within their locality. However, it was also an era that was driven by strong relationships between retailers and consumers, especially knowing the customer personally, and offering hyper-personalised recommendations as well as benefits like credit/khata to regulars with good relationships. There was also a definitive air of ‘assured fulfillment’ as retailers would take orders from the customers and go out of their way to fulfill it for them by getting the required goods from their networks. It was an era of personal bonding that is still seen among smaller stores (local kiranas for example) in metros and neighbourhood stores in smaller towns and cities.

The O+O (offline and online) era

With the boom of e-commerce, major players like Flipkart, Amazon, Shopclues, Myntra etc ushered in the era of mobile shopping. With the backing of evolving technological platforms, burn money, and increasing smartphone/internet penetration, the driving forces behind this era were availability, accessibility, and affordability. The pace of technological integration combined with unequal distribution of internet access made it difficult for offline retailers to adapt to this wave. The wild wave of discounts, EDLP, and signup offers drastically changed the power structure and the power shifted to the consumer. Although tech has tried very hard to bring the experience of ‘knowing what you want’, but has ended up largely being intrusive and sometimes, annoying. On one hand, the customers lost out on more human touch, on the other, they gained the convenience of all in one place.

Collaboration era

According to a 2020 Mckinsey report, around 96% of consumers have adopted new shopping behaviour, and approximately 60% of consumers will make the shift to online shopping in the festive seasons and continue it in the ‘new normal’. One of the fastest-growing consumer segments of the past year for eCommerce has been the 50+ category. The pandemic and the lockdown have led to one of the most significant shifts in the way we shop. Whenever we decide to buy something that is beyond a staple/necessity, we now Google for options. Psychologically, we are getting more digitised.

While the rise of digital acceptance has led to increased online shopping, the initial days of the lockdown exposed the fact that e-tailers did not have enough infrastructure in place to fulfill the drastic adoption. This led to people going back to relying on neighbourhood stores. Brands noticed and one of the key changes that came into place was online players working alongside local offline players to not just fulfill orders, but also help deliver on convenience.

The driving factor for this era will be dependent on brands nurturing on-ground relationships with sellers/outlets/GT Owners and no longer see them as competitors but as partners in inclusive growth. Thus, leading to convergence of channels and a shift towards true omnichannel experiences.

Experience is the key

In the past year, as businesses were still going through major overhauls to adapt, having to adopt a hybrid business approach became increasingly popular among offline retailers, especially small business owners. The most common and prominent examples being local kirana stores accepting orders through platforms like WhatsApp and contactless payments while offering doorstep deliveries – thus, adding a convenient experience to their arsenal.

E-commerce brands witnessed a massive spike in orders from tier II and III cities and towns. This has been a trend in the past few years but amplified with lockdowns and wide acceptance of digital payments. Even in these regions, shopkeepers adapted to UPI payments and began adding QR codes to their cash counters.

The theoretical blurring of boundaries between ‘online’ and ‘offline’ sales channels has been spoken about for years. But these behaviours are on full display today:

- People planning their visits to stores more carefully, while looking for availability on online channels.

- Customers wanting to know whether a store offers online ordering with in-store pickup.

- Another common behaviour change is checking for prices/offers online while shopping in a supermarket for better offers.

Consumers today need reassurance that they’ll find what they’re looking for before they leave home. The necessity for legacy retail brands to have a strong e-commerce presence grows every year, at the same time, digital-native brands are opening brick-and-mortar stores to attract new customers. These behavioural shifts are driven by convenience and are centered around the promise of a seamless shopping experience.

Convergence is simply convenience

Brands that will stand at the top of the ‘collaboration era’ will have to seamlessly mix both traditional and online channels into a digitally enabled ecosystem. This includes understanding and creating O+O experiences by leveraging the right tech solutions and digital-savvy employees and customers. This ‘hybrid’ model will be the mainstay retail model as research predicts that 78% of purchases[9] will still be made in stores by 2024.

Brands can no longer depend on a traditional ‘path to purchase’ in the expectation that a consumer will be pulled into the funnel. They will have to reframe the journey and look at it from a different, proactive perspective – a path to sell:

1. Identify (Using a combination of data-led insights and hardcore offline research)

- Buying behaviours (Guided by convenience)

- Trends (Their adoption from a long-term POV)

- New platforms/channels (Emerging out of necessity or innovation)

2. Collaborate (To provide the right products, services, and benefits)

- Technological interventions (Taking advantage of the merging of O+O)

- Logistical innovations

- Partnerships for scale

3. Deliver (On brand promise and provide a seamless experience)

- Touchpoint options

- Purchase options

- Delivery options

- Personalisation options

- Loyalty options

With increasing consumer familiarity with digital, what we define as a ‘path to sell’ will act as a guideline for the transformation of traditional retail. The outcome of this transformation of the retail sector will be a more personalised experience, simplified digital operations, integrated supply chain, with fintech acting as the backbone. The idea of adopting this approach is to keep the brand at the intersection of convenience and share of attention while aiding the consumer in finding ‘the one’.

This article was originally published in Campaign India.